Gahan Wilson is dead.

I'd make a joke about it, but nobody joked ever about Death as well as Gahan, or, I suspect, for as long.

His stepson describes him, in his death announcement, as "one of the very best cartoonists ever to pick up a pen" and he was.

He was a gentle, funny, charming man. One of the most perfect evenings I've ever had was the night that Peter Straub and Gahan Wilson and I wound up after an event in the little lobby bar at the Royalton Hotel, back when it was a Philippe Starck-designed place, and the three of us, in our uncomfortable tuxedos, talked about art and puppets and humour and horror and Sherlock Holmes and and what we were trying to make until late into the night.

Ten years ago, I had the honour of writing an introduction to Gahan's book, 50 Years of Playboy Cartoons.

This is what I wrote:

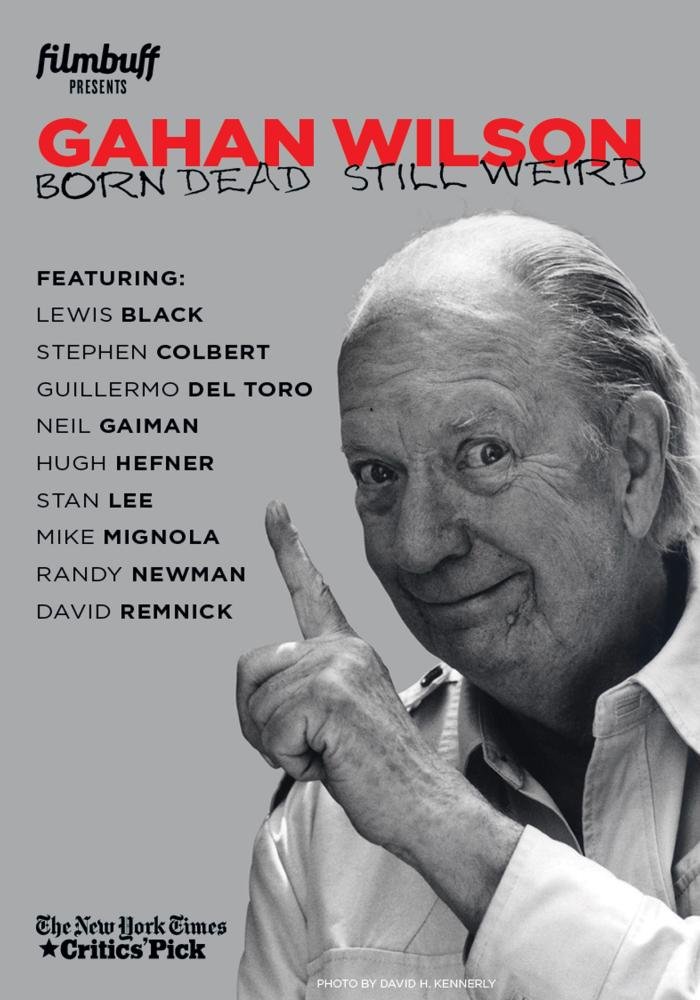

Here's the animated film I talk about above.

I'd make a joke about it, but nobody joked ever about Death as well as Gahan, or, I suspect, for as long.

His stepson describes him, in his death announcement, as "one of the very best cartoonists ever to pick up a pen" and he was.

He was a gentle, funny, charming man. One of the most perfect evenings I've ever had was the night that Peter Straub and Gahan Wilson and I wound up after an event in the little lobby bar at the Royalton Hotel, back when it was a Philippe Starck-designed place, and the three of us, in our uncomfortable tuxedos, talked about art and puppets and humour and horror and Sherlock Holmes and and what we were trying to make until late into the night.

Ten years ago, I had the honour of writing an introduction to Gahan's book, 50 Years of Playboy Cartoons.

This is what I wrote:

GAHAN WILSON INTRODUCTION

I have an embarrassing admission to

make: when I was a barely pubertal schoolboy I did not look at

Playboy for the articles. I did not actually care about the

articles. Interviews with American

politicians or movie stars left me unmoved, reviews of stereo

equipment or sports cars or cocktails meant nothing to me. No, I went

to Playboy for the

pictures.

I was

not old enough to buy it, nor brave enough to steal it, so each month

I would head into my High Street W.H. Smiths, and go up on tiptoes,

and reach up to and take Playboy down

from the topmost

shelf. Then I would slick through it as rapidly as possible, past

the Playboy Advisor,

past the naked ladies (pneumatic, terrifying creatures, quite unlike

the girls at local schools I would stare at awkwardly and with

longing when I passed them on the street), past the short stories

(even if I wanted to read them there would not be time before a shop

assistant spotted me), until I found it. It was always there: the

Gahan Wilson cartoon. And I would stare at it, at the strange,

squashed Plasticene-faced people, at the vampires and the people

building monsters, at the enormous aliens and raggedy mummies and

acts of unspeakable cruelty and nightmare (“What's the matter? Cat

got your tongue?” asked one spouse of another. And under the seat

was the cat, and it had.)

In a magazine

devoted to sex and aspirational lifestyle accoutrements, Gahan Wilson

was about something else – a cock-eyed, dangerously weird way of

looking at the world. Even when sex entered the picture it did so

strangely and awkwardly (Superman, his back to us, flashes an old

lady, who, unimpressed, retorts “You're not so super.” Vampires

view sleeping nubiles as snacks. Werewolves... ah, you'll find out.)

And,

strangely, the knowledge that each Playboy had

a Gahan Wilson cartoon in it somehow, for me, made Playboy

cool in a way that the cars and the cocktails never could, just as

the knowledge that Charles Addams was forbidden to draw the Addams

Family characters in the pages on the New Yorker

made that respectable magazine significantly less remarkable in my

eyes.

Over

the last two decades I have had the good fortune of encountering

Gahan Wilson in the flesh: initially, oddly, as a book reviewer who

said nice things about what I did. I wrote him a fan-letter, got a

wonderful letter back from him with a drawing of Mister Punch on it,

and finally got to spend time in his company at a variety of

conventions and meetings across America. Art Spiegelman and Francoise

Mouly teamed us up for their Little Lit book,

and I wrote a story for Gahan to draw that meant that I found myself

interviewed when they made a documentary about him (Born

Dead, Still Weird) and that the

comic we did was beautifully animated for the movie: it had ghouls in

it, and small children, and dead people, all of which traditionally

show up in Gahan Wilson's work.

In person, Gahan is

tall. His face might possibly have been made out of Plasticine, but

he is – and I doubt he will mind me telling you this –

significantly better looking than many of the people, some of the

monsters, and all of the aliens that he draws. He is, in person, a

funny man, not with the compulsive joke-making look-at-me funny of

comedians, but with a comfortably wry view of the world that he

communicates with ease. He is affable and intelligent. He does not

seem like a cartoonist – were I to pick a profession for him based

on his looks it would be that of successful small-town mortician, I

think, or owner of a backwoods motel. Or an alien, squished

uncomfortably into a Gahan Wilson-shaped humanoid body suit, here to

observe our ways and taste our wine and despoil our women.

He

operates in no tradition, although, on occasion I have seen people

and line in nineteenth Japanese prints and, in one case, a

five-hundred year old graffitied drawing of a monk and a dragon on

the side of a Chinese temple that I could have sworn were made by

Gahan Wilson's pen. He draws on horror movies, on popular culture, on

his own strange view of the world and of the permeability of language

– not punning, but playing with words and popular expressions in

ways that flex and stretch them, like a morbid poet. (“Is Nothing

sacred?” asked a man in a place where they worship Nothing. “How

are they selling?” is asked of a sad-looking man with piles and

piles of unsold hot cakes.)

Until

now it was hard to be a real fan of Gahan Wilson's Playboy

work. I do not read every issue

of Playboy, for a

start, and these days the magazine is too often sold wrapped in

plastic. And when Gahan Wilson's cartoons have been collected in the

past, the Playboy cartoons

were often black and white reproductions of the colour originals.

This book made me happy and excited when the publisher told me it

would exist, and it makes me happy and excited now – the idea of

getting to see the Gahan Wilson Playboy cartoons

as they were meant to have been seen, all of them collected together

chronologically is one that I find intrinsically wonderful. The world

is a better place for having this book in it. No kidding, no

hyperbole (well, maybe a little. But I mean it, so that makes it all

right).

I'll shut up now

and get out of the way. You have pictures to look at that will make

your world more interesting. I don't know if these cartoons will

taste the same without me having to do that nervous top-shelf dash.

Possibly they will be better.

I trust these

volumes will sell like hot cakes.

Neil Gaiman

They were cartoons like this...

I got to reprint one of his short stories in the book Unnatural Creatures, a benefit book for the Washington DC literacy program 826 DC. It was not actually called

although sometimes it's called (Inksplot).

Here's the animated film I talk about above.

It's a short film that was made for the documentary BORN DEAD, STILL WEIRD, as an adaptation of the short story we did together for Francoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman's IT WAS A DARK AND SILLY NIGHT book.

I really really liked Gahan. He was one of the people you admire before you meet them who live up to your expectations and hopes when you do. I'm deeply sorry he's gone.

It seems like last week that I bought a drawing from him, the cover art for a book I wrote with Gene Wolfe, A Walking Tour of the Shambles.

We used to talk (half-joking, but only half) about doing another volume of Little Walks For Sightseers, but 2019 took Gene and now it's taken Gahan, and I miss their conversations and I wouldn't want do it on my own.

Labels: Gahan Wilson